The Book

Researched in the 1960s and 70s, it is likely that this is the first geo-ecological doctoral thesis to be produced in Africa, and one of the few truly holistic ecological studies of a region ever to be published.

Montane to Mangrove takes into account the geomorphology and water catchments of the Gorongosa region, the geology, the soils, the drainage processes, the climate and

air movements, the vegetation patterns, animal distribution (including human) and the ongoing relationships between all of these.

From this kaleidoscope of facts Tinley draws practical and far-seeing

conclusions using salient factor analysis and overlay mapping. These conclusions led to recommendations for working with nature to co-create the future sustainability of the region and its elements.

However, what is written in this book is not only applicable to Gorongosa National Park. These techniques can be used in most lands of our Earth and have for the past 20 years been in practice in Outback Australia to regenerate grasslands and savannas of overgrazed pastoral lands

Ken Tinley’s thesis is available for purchase at 150 USD plus shipping. If interested, please email Megan Carolla at megancarolla@gmail.com.

About the Author

Ken was born in South Africa in 1936 and grew up amongst the Natal midland forests and grasslands where he learnt his basic ecological knowledge from the local Zulu people. After high school he worked 6 years as a game ranger in Northern Zululand during which time he completed ecological surveys of the lakes and river systems. At age 26 he started university, achieving over the years B.Sc. (Earth and Life Sciences, Natal University), M.Sc. (on the Okavango Delta, Botswana) and D.Sc. in ecology and natural resource management (on Gorongosa at Pretoria University).

Ken’s proficiency in reading landscape patterns and processes grew as he worked in the field interrelating earth and life sciences. On low-level air flights he identified patterns, processes and trends; ground-truthing followed for map recording, planning and management solutions (including photographic record).

Fifty-five years were spent in rangeland studies and land management/conservation from extreme deserts in southern Africa and Saudi Arabia; to the savannas of central Western Australia, Northern Territory and Kimberley; to the tropical savannas and forests of central Mozambique.

In 1984 Ken, Lynne and their three children moved to Western Australia. At this stage of his life Ken secretly hoped to give up conservation work and become a full-time surfer! This was not meant to be and he worked for the local nature conservation department as well as doing consulting projects overseas (including one back in Gorongosa National Park in 1994).

In January 2000 he originated an extension program, based on his Mozambique work with rural neighbours of the national parks, for pastoralists and land care groups in the arid mulga savannas of Western Australia. This program, Ecosystem Management Understanding (EMU) was judged in 2005 by two independent assessors the most successful rangeland extension work ever done in WA.

Ken and Lynne are now retired and living in Fremantle on the coast of Western Australia..

“Ken Tinley’s D.Sc. thesis is a masterpiece. He’s a tremendous intellect and a visionary, we really respect and appreciate what he did, and we are going to make sure that his pioneering work is clearly acknowledged in everything that we ever do that draws on his research, from now until I’m his age.

There’s no way he could have been conscious at the time of how valuable his work was going to be — and in what ways. “

Robert M. Pringle, Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, Princeton University

Foreword by Greg Carr

I saw Gorongosa National Park for the first time from a helicopter on March 30, 2004. It looked magnificent from above. There were multiple forest and woodland types, grasslands, rivers, a lake, and fascinating geological formations. When we landed, however, it was clear we had trouble. The historic Chitengo Camp lay in ruins—former buildings were rubble. Where tourists once wandered, burned-out vehicles lay amongst grass that was higher than my head. That year, the Mozambican government asked me to help restore Gorongosa, once one of the most popular wildlife parks in all of Africa.

In the 1960s, scientists said that Gorongosa had the densest abundance of wildlife of any natural area on the continent. This was no longer true. On our visit in 2004, we could drive an entire day and see perhaps one warthog or one baboon. Whatever other wildlife there was hidden in dense forests and had every reason to fear vehicles. Approximately 95% of the large animals were killed during and in the aftermath of one generation of war. How could we possibly restore a landscape of 400,000 hectares (one million acres)?

If we were going to help the Government of Mozambique re-wild this ecosystem, we needed to understand it. We needed to create a Park Management Plan.

My very small team and I searched the literature. We found popular accounts of Gorongosa in newspapers and even in the prestigious National Geographic Magazine, dating back to the early 1960s. However, we also needed scientific data. A Harvard University friend found a reference to a doctoral thesis called Framework of the Gorongosa Ecosystem published in 1977 by a Kenneth Lochner Tinley, but not the actual thesis. At the time, Google was a ‘child’, just six years old, and one did not find nearly every imaginable piece of information online. We learned that a physical copy of the thesis existed at the University of Pretoria, South Africa. We used ‘interlibrary loan’ to get that actual document (not a facsimile) sent by the postal service to Harvard and then to us. Helping me was Sydney Kwiram—a brilliant young woman and recent Harvard graduate.

The manuscript’s abstract included this paragraph: “The chapter titled ‘Process and Response’ is the central pivot of the thesis containing the kinetic aspects of geomorphological landscape changes with coevolutionary sequences of biotic communities which change (expand, contract and recombine) kaleidoscopically in space and time, in appearance and content.”

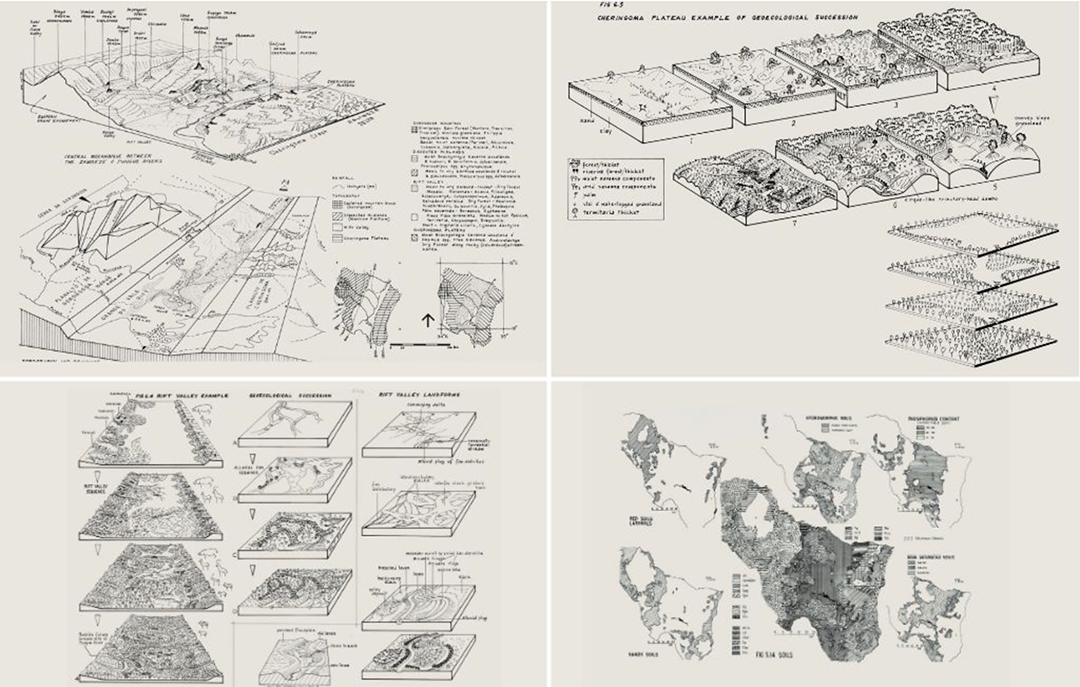

Wow. I am not a biologist. I wondered if I should return to the friendly, popular newspaper articles about Gorongosa! However, the Tinley masterpiece is written by an incredible hand. It is the kind of literature that a layperson can follow if one reads carefully, even as an expert will gather much more from the same page. Sydney and I devoured this tome. The thesis had chapters on landscape setting, geology, soils, hydrology, climate, wildlife—covering an area in central Mozambique larger than the Park boundaries themselves—under the labels of “Gorongosa Mountain Summit”, “Gorongosa Mountain Slopes”, “Midlands”, “Rift Valley”, “Coast Plateau”, and “Land-sea Junction”. There were graphs of data and hand-drawn maps by Dr Tinley. He did all of this prior to the existence of the personal computer, GPS, digital photography, drones and the Internet. He with his spouse, Lynne Tinley, and their two small children lived in Chitengo (the place where I had landed in March 2004) from 1968 to 1973.

WHERE ON EARTH IS DR TINLEY?

We had the document, but what about Ken Tinley? Was he still alive? Did he live in South Africa? We would not find those answers in 2004.

Meanwhile, our team of scientists used insights from the Tinley thesis as we wrote a proposal to the Government of Mozambique to co-manage and restore Gorongosa. Among many critical observations, Ken Tinley—speaking through his thesis—told us that, in order to save the ecosystem over the long term, Mount Gorongosa needed to be added to the Park. Mount Gorongosa holds one of only two true rainforests in Central Mozambique, full of endemic and near-endemic species. The mountain is the critical source of most of the Park’s surface water during the dry season. At this time, it did not have protected status.

We continued our studies, our visits to Gorongosa, and our talks with the Government of Mozambique. I expanded our team. In 2005, on one of the luckiest days of my life, I met Vasco Galante. Vasco became the Director of Communications for the non-profit ‘Gorongosa Restoration Project’. He is a human connector: he makes friends, then he becomes friends with their friends. He remembers everyone, every encounter, every event. We call him ‘Vascopedia’. Vasco’s records tell me that we found Ken Tinley in 2005. I sent him an email (which, of course, Vasco saved) on November 28, 2005, that says: “We are in communication with Dr Tinley (who now lives in Australia), and we have his thesis, which you will enjoy. I’ll ask Bridget to send you a copy.”

“In communication with Dr Tinley” actually meant that we had found an email address for his spouse Lynne (from someone who knew someone) and contacted her. Lynne is equally brilliant and is Ken’s lifelong teammate. She is an artist of Nature. She wrote Drawn from the Plains, a book about living in Chitengo Camp, Gorongosa Park’s headquarters, for five years. The book includes her original artwork. We located a copy.

I remember reading my first email reply from Lynne. I now felt that the legendary Gorongosa of the 1960s was no longer just a storybook place to read about in articles. I was talking to someone who had lived there, seen it, smelled it, heard it, and breathed it. Soon, I started receiving messages on Lynne’s email account written by Ken. I was finally talking to the person who had written Framework of the Gorongosa Ecosystem when I was still in middle school.

We corresponded with Ken steadily from 2005 on, sharing ideas and receiving welcome advice. Ecologist Dr Marc Stalmans was a consultant to us and later became Director of Science for Gorongosa National Park. He helped us plan the restoration. “Ken was truly ahead of his time,” Dr Stalmans explains, “applying a landscape ecological perspective well before this approach gained popularity in the 1980s-1990s. Ken manually applied GIS principles before the electronic tool was available. Whereas many studies conventionally only provide a snapshot in time, Ken’s work takes a long term, geomorphic and geo-ecological view of the Park in terms of the formation, evolution and long-term outcome of its ecosystems and constituting components. That’s why the work is still hugely relevant one half-century later. Even more astonishing is that this magnum opus resulted from Ken spending only five years in the Gorongosa ecosystem.”

Hand-drawn images from Ken Tinley’s thesis. Clockwise from top left: Salient landscape features; Cheringoma Plateau example of geo-ecological succession; soil map; Rift Valley example of geo-ecological succession

On top of that, Dr Tinley still found time to sketch landscape perspectives of Banhine National Park in Mozambique and an area next to the Kruger National Park in South Africa that would later become part of the Limpopo National Park. Thirty years later, in the early 2000s, these perspectives became the foundation for the first landscape maps for both parks, which now form part of the Greater Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area.

In 1990, well after his five years living in Gorongosa Park, Ken worked with landscape architects in Pretoria. They agreed that the existence of a large number of national parks and nature reserves along the frontier between Mozambique, South Africa, Zimbabwe and Swaziland opened the possibility for multi-national transfrontier resource areas (referenced by Dr Stalmans above).

It was exciting to think that existing protected areas could be linked by some of the little populated areas in between—to create one of the largest conservation zones in the world. Rural communities living within the resource areas, as well as the governments of the various countries, would benefit. Ken was one of the originators of the idea that became known as ‘Peace Parks’.

We completed the first draft of our Park Management Plan and finalised our co-management contract with the Government of Mozambique. In January of 2008, I signed a 20-year agreement with the Government to co-manage and restore the Gorongosa ecosystem and to bring human development services to the communities that live adjacent to the Park. (That agreement has now been extended to 35 years, until 2043.)

In 2008 we revitalised the ranger team. The team began removing wildlife traps and snares from the Park; some left over from the war. We started a health care programme in nearby communities. We began our first attempts at tourism.

MEETING KEN TINLEY

Yet, I had still not met Ken Tinley. I invited him to come and see what we were doing. In October 2010, Ken spent five days with us in Gorongosa.President Nelson Mandela, a founder of the Peace Parks Foundation, believed national parks could link nations or regions that had previously seen conflict. His theory: The connected ecosystems would be good not only for wildlife but deliver benefits and peaceful relations to people as well.

Clockwise from top left: Bob Poole (camera), Mateus Mutemba, Fernando Ussene, Ken Tinley, Tonga Torcida and Vasco Galante; Ken Tinley, Vasco Galante, Fernando Ussene; Greg Carr and Ken Tinley; Ken Tinley

On the last day of his visit, Ken shared a poignant story with us. This trip was not the first time he had been to Gorongosa since 1973. In 1994, after the war ended, Ken and a man named Paul Dutton, along with José Tello (ex-warden of Gorongosa), were contracted by the IUCN to survey the condition of the National Park. Like Ken, Paul had begun his career as a Game Ranger in the Zululand Provincial Game Reserves and later continued his education to earn a graduate degree in Ecology. They became lifelong friends. In his own small Piper Cub airplane, Paul helped Ken and José perform the first aerial surveys of the vast herds of large ungulates during the first year of Ken’s research in Gorongosa. In 1994, they found what I saw a decade later: no wildlife and destroyed infrastructure.

THE FUTURE

The Gorongosa Restoration Team has made great progress from 2010 to 2019. Our rangers removed over 27,000 traps and snares. We reintroduced some species that we obtained from other national parks, such as buffalo and wildebeest from Kruger. But mostly, in a safer environment, the remaining small populations of wildlife were able to increase on their own. In 2018 we conducted an aerial wildlife survey and counted more than 100,000 large animals. (This represented just the fifteen largest species we could count from the air, not the innumerable smaller species that are also thriving.) The press has been kind to us. National Geographic refers to us as perhaps Africa’s greatest wildlife restoration story.

Group of children singing on their way to Girls Club, a Park initiative that supports girls education.

We also made headway on our human development programme in the traditional communities that share the greater ecosystem with the Park. Our after-school Girls’ Clubs keep teenage girls in school and out of child marriage. We help small farmers get better yields on their land. We’re restoring the rainforest on Mount Gorongosa by planting shade-grown coffee. We provide healthcare to more than 100,000 people per year.

This idea that national parks should benefit the local people was one of Ken Tinley’s early insights and it forms the core of our philosophy at Gorongosa Park. But not only that, we also believe that local people should lead the management of these protected areas. They have knowledge and expertise about the healthy functioning of these ecosystems that they have inhabited since time immemorial. and they can combine that wisdom with 21st Century ecological science.

During the Colonial era, most Mozambicans were not allowed to go to school beyond the fourth grade. It is a painful and unpleasant fact, but one we should remember. At the Gorongosa Project, our goal is to empower the next generation of Mozambican scientists who will lead this ecosystem to the 22nd Century. They face of a new set of challenges, perhaps even greater than the wars of the 20th Century – climate change, pollution, invasive species, habitat loss and over-harvesting. Thus, we created a Master’s in Conservation Biology, a two-year program located in the park. It is the only master’s programme in the world taught entirely within a national park. We’ve already graduated our first cadre of twelve Mozambican women and men. The second group will finish at the end of 2021.

We also help Mozambicans continue their education to earn PhDs. Dominique Goncalves, a Mozambican woman who grew up near Gorongosa, is completing her PhD in Wildlife Ecology at the University of Kent in the UK. She also is the Manager of Elephant Ecology at Gorongosa Park. In October of 2018, I travelled with Dominique to Perth, Australia, to meet Ken and Lynne Tinley in their home. The walls of their apartment were covered with Lynne’s original artwork, some paintings of Gorongosa. Ken and Dominique talked for two days. He gave her unpublished notes from his research as the two of them exchanged ideas, passing the torch of Gorongosa science to the next generation.

Greg Carr

April 14th, 2021.

Ken Tinley handing his valuable knowledge to Dominique Gonçalves, manager of elephant ecology in Gorongosa, in Perth.

Ken Tinley’s thesis in hardback is available for purchase at 150 USD plus shipping. If interested, please email Megan Carolla at megancarolla@gmail.com.

In addition, there is a digital copy available here.